Text: M. Zisso; Photo: Archive

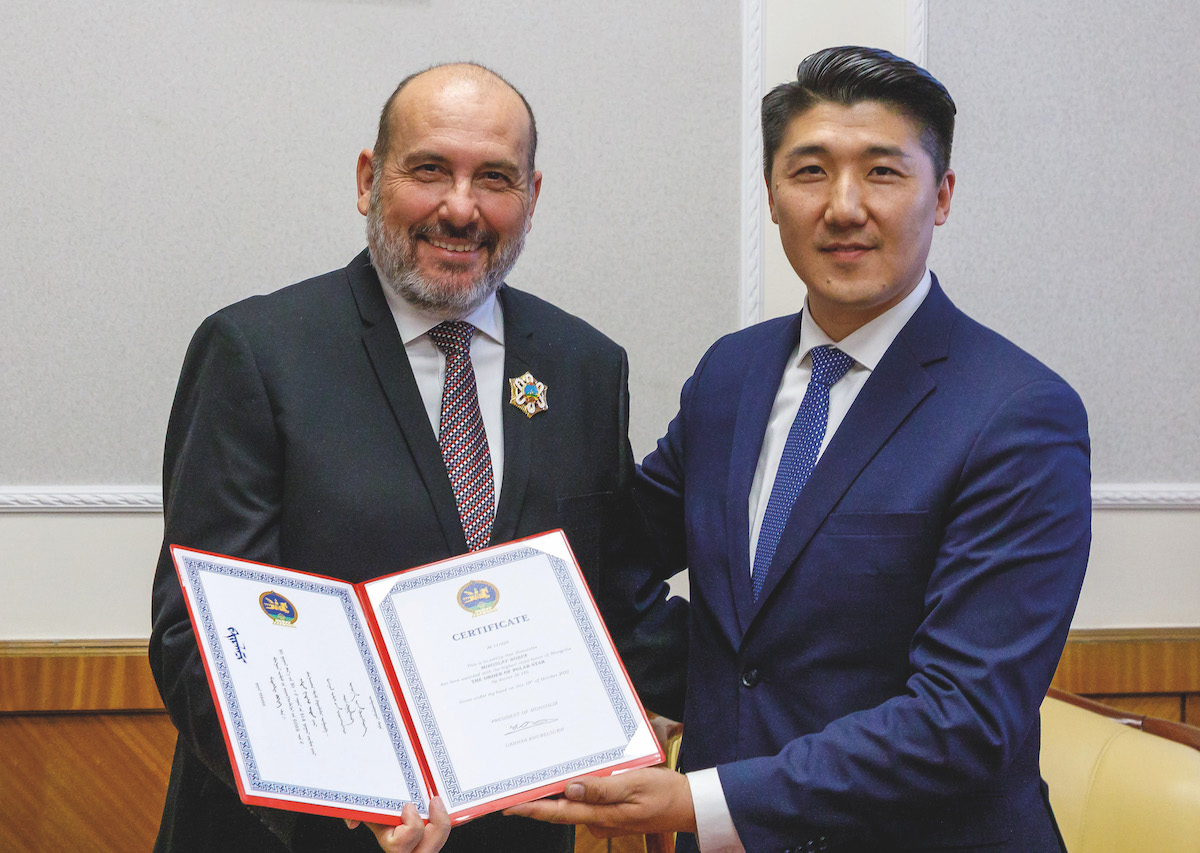

Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh awarded Miroslav Bobek, Prague Zoo’s director, the “Order of the Polar Star” – the highest state decoration a foreign national can receive. The president’s advisor, Erdenetsogt Odbayar, presented the Order on the president’s behalf, and thanked Mr Bobek for his outstanding contribution to Mongolian nature conservation and the development of Czech-Mongolian relations.

Under the leadership of Miroslav Bobek, Prague Zoo, in cooperation with the Czech Army and a number of other organizations, has carried out a total of nine air transports of Przewalski’s horses to western Mongolia. However, it has also been supporting the long-term sustainability of their return to the wild and is now preparing a reintroduction project for eastern Mongolia.

“The awarding of the Order of the Polar Star is a great honour for both the current and past staff of Prague Zoo. They have contributed decades of hard work to rescuing the Przewalski’s horse and returning it to its original homeland,” said Miroslav Bobek on this occasion. “This award comes at a time when the twenty-nine mares we transported to Gobi B by CASA aircraft not only have had over eighty foals, but also ten grandchildren and even their first great-grandchildren. Our mission in western Mongolia is accomplished, we are now turning east.”

Miroslav Bobek went on to say that Prague Zoo’s projects for biodiversity conservation would be unthinkable without the support of the zoo’s founder and the public. He pointed out that five Czech crowns from every entrance fee to the zoo go to these projects.

Jan Vytopil, the Czech Ambassador to Ulaanbaatar, highlighted this award’s significance by stating “The award shows just how much Mongolia appreciates this Czech project for reintroducing Przewalski’s horses. The project is all the more important in a world that is facing a major decline in biodiversity everywhere.”

Przewalski horses in the area where they survived the longest and where they successfully returned – the Dzungar Gobi – also thanks to our zoo

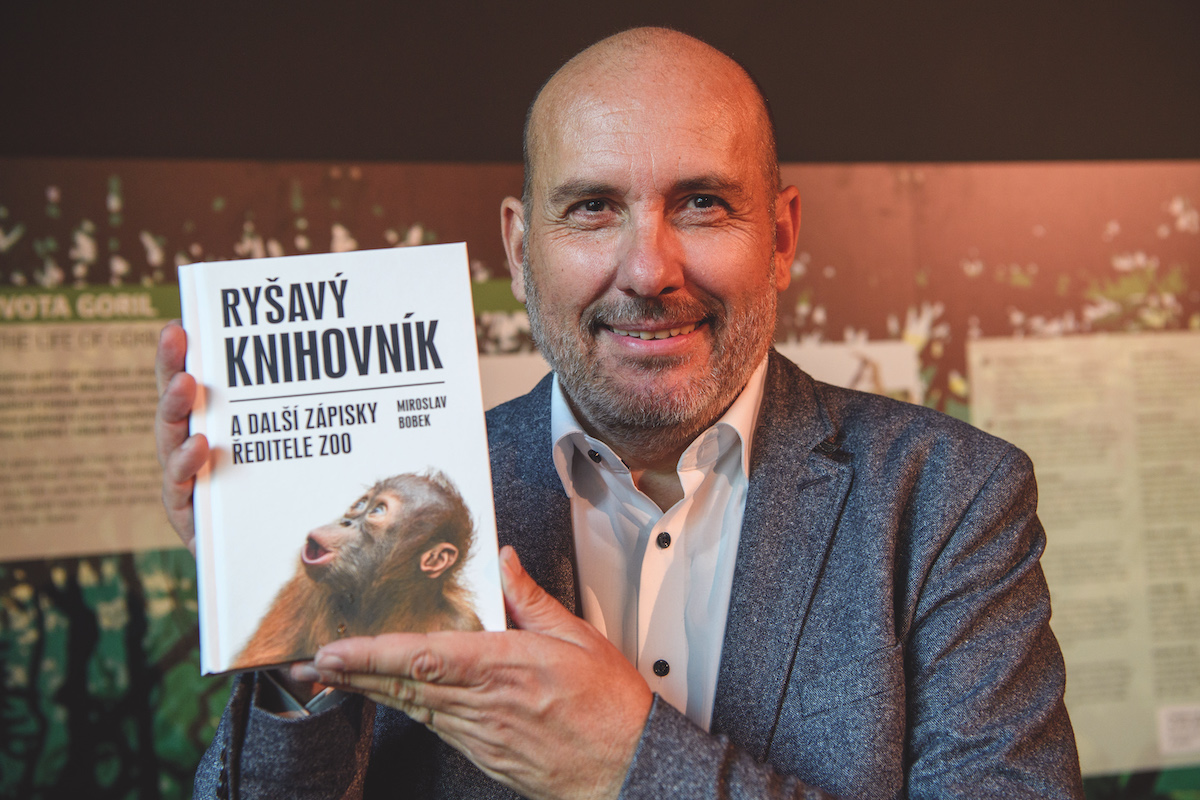

Prague Zoo’s director shares his experiences regularly with the readers in his books. The first was published 10 years ago and was called “Bobbles from Bobek”, the latest came out this September under the Czech title “Ryšavý knihovník a jiné zápisky” and its Czech version is already on sale. The full English version is now on sale as well. In the Czech & Slovak Leaders magazine, you can find the four chapters dedicated to wild horses:

- The Last Wild Horse (Hopefully) without Question Marks

- Wilderness in the Scenery of the Metropolis

- A Century after Ali’s Arrival to Prague

- The Return of the Wild Horses – Heading East!

1) The Last Wild Horse (Hopefully) Without Question Marks

The scientific paper published last year by Timothy T. Taylor and Christina I. Barrón-Ortiz may not have a very catchy title – Rethinking the Evidence for Early Horse Domestication at Botai – however, it is very interesting. After reading it, I remembered one of my favourite kaleidoscopes. Simply turn it around and the coloured glass would rearrange to form a new, radically different pattern. The work in question is also like turning a kaleidoscope. Suddenly, it gives us a completely different picture.

It was assumed for quite a long time (although not everyone agreed) that the roughly five and a half thousand-year-old skeletal remains of horses found in northern Kazakhstan might well be the oldest evidence for their domestication. That it was the people of the Botai culture who bred and used these horses as livestock and riding animals, and that maybe it was these horses that gave rise to modern domestic horses. Examples of the evidence for the domestication of the Botai horses were provided by marks from bits on the preserved teeth or the vestiges of pits filled with decayed vegetative matter, which was thought to be the remains of horse dung.

A significant change to the majority view of Botai horses came in early 2018 with the work of 47 authors led by Charleen Gaunitz. It was entitled “Ancient Genomes Revisit the Ancestry of Domestic and Przewalski’s Horses”. Based on genetic analyses, it showed that the horses from the Botai culture were not the ancestors of our domestic horses (including mustangs and all other feral forms) and that they were much closer to another lineage – namely Przewalski’s horses. According to one of the extreme interpretations of the results obtained, Przewalski’s horses could even be the feral descendants of the domesticated horses of the Botai culture. If that were the case, then the Przewalski’s horse would be the only remaining representative of a unique lineage of horses, but not the “last wild horse”.

Cut and change the image again, now directly related to the work cited in the introduction. In it, Taylor and Barrón-Ortiz recapitulate the reasons why Botai horses cannot be considered domesticated. One of the weightier ones is the fact that the animals’ age composition, deter- mined from the skeletal remains, does not correspond to the age structure of horses in captivity. The authors then focused on assessing the damage to the teeth that was thought to have been caused using a bit. Amazingly, they found identical damage on the teeth of wild Pleistocene equids from North America! Thus, they were able to state that the damage found on the teeth of the Botai horses was probably caused by natural developmental defects and wear, rather than by contact with a bit. This is, of course, a very strong argument in support of their claim that the Botai horses were not domesticated; rather they were wild Przewalski’s horses that had been hunted extensively by the people of the Botai culture. What’s more, the bone finds come from places that seem to be made for such hunting.

Now the likely theory is that the Przewalski’s horse is not a feral descendant of a horse that was domesticated aeons ago, but it is, in fact, what we have always considered it to be: the last, and therefore currently the only, wild horse.

2) Wilderness in the Scenery of the Metropolis

On Monday afternoon, we released four Przewalski‘s horse mares into the almost twenty-hectare enclosure at Prague’s Dívčí hrady. Shortly after, when I saw two of them on the horizon with Prague’s Pankrác district in the background, I felt like I was in Nairobi National Park, where the high-rise buildings of the Kenyan capital loom behind giraffes.

As expected, releasing the mares, transported from our breeding station in Dolní Dobřejov, attracted considerable media attention. Another activity, which took place two days earlier, we didn’t even announce as it was far less conspicuous, although it was equally important to us: We released about one hundred and sixty crucian carp into the former mill race on the grounds of our zoo. It was the first step to help the return of this once completely common, but today extremely endangered fish, not only into our grounds, but, hopefully, into other Czech rivers and water bodies.

Releasing the Przewalski‘s horses at Dívčí hrady and the crucian carp in the former mill race in the zoo are both examples of our efforts to preserve the biodiversity of the local fauna and flora. Although our activities aimed at global conservation have gained far more renown, at least so far, our domestic efforts also have a relatively long history. For the most part, however, they have focused mainly on Prague Zoo’s grounds. For instance, the European ground squirrels did not simply turn up in the area below Sklenářka, it was all due to our colleagues, who released them there and then spent many years ensuring that their colony prospered.

An exemplary illustration of these activities is the revitalization of the zoo’s rock massif. Here we laboriously cut down false acacias and other unwanted vegetation, so that the bushy rock steppe and the vineyard once planted here could return. This restored environment has given many plant and animal species a valuable foothold, with perhaps the most visible indicator being the increase in the population of the critically endangered European green lizard. Just as a reminder: the main aim of releasing the Przewalski‘s horses at Dívčí hrady was also to restore the local steppe habitat.

Even though, despite the pandemic of COVID-19, we continued in 2020 and 2021 our efforts to develop our conservation projects around the world, our appetite for our domestic ones also increased. Having released the Przewalski‘s horses at Dívčí hrady, in the southwestern part of Prague, we started planning and later also undertook preparations to place European bison into a corral in the northeast of Prague. Now that’s something to look forward to!

The mares of Przewalski horse with the background of urban scenery, in the enclosure at Dívčí hrady

3) A Century after Ali’s Arrival to Prague

Three weeks after Prague Zoo celebrated its ninetieth birthday on September 28, 2021, a century had passed from the day when the first Przewalski’s horse arrived to Prague. It was Ali, the stallion, which the hippologist Prof František Bílek obtained from Halle. Bílek accommodated him to a school farm in Netluky at Uhříněves. It happened on October 17, 1921. Later, on January 23, 1923, the mare Minka followed. And these were the two Przewalski’s horses who became the founders of Prague breeding. Thus began the long journey which culminated with The Return of the Wild Horses to Mongolia.

However, in relation to one hundredth anniversary of Ali’s arrival to Prague let’s have a look not on what followed, but on what preceded the event. What was the journey of the last wild horses from central Asia to the West? General Nikolaj Przewalski obtained the first skull and skin of a Przewalski’s horse in 1878; the scientific description was done three years later. The first living Przewalski’s horses came to the natural reserve Askania-Nova (then in the Russian empire, today at the occupied part of Ukraine) in March 1899, and later more individuals followed them to Russia. However, at that time, the biggest and from our point of view the most important expedition was already underway, financed by German animal dealer Carl Hagenbeck. Its goal was to bring Przewalski’s horses to the West.

Hagenbeck entrusted a merchant Wilhelm Grieger with the organization of the entire event, who, after various mishaps, set off to Kobdo, todays Khovd, in the winter of 1900 – 1901. At that time, it was a Chinese fortress with about 1,500 inhabitants; today it is an administrative centre of the ajmag of the same name in western Mongolia with 30,000 inhabitants. As Hagenbeck later described, Grieger reached it by taking first the Siberian railway by Moscow to Ob, then from Ob by sledge about 250 versts (one verst is 1,066.781 metres) to Biysk and then with a lot of supplies and material he continued 700 versts on horses and camels. In Kobdo then with a help of Russian merchant Asanov, who already arranged capture of Przewalski’s horses for Baron Falz-Fein, he hired one hundred of Mongols and set off with them to look for wild horses.

The captures of the horses occurred at three places from 250 to 300 versts south of Kobda, in the area where we are returning the horses now. The capture process Carl Hagenbeck later described as follows: “The horses have a habit to lay down at the watering hole for several hours. Hordes of Mongols with their horses sneak to- wards them, taking cover, and at a given signal the entire company loudly shouting pounces on the resting horses that jump up and race into the steppe in terror. Only a huge cloud of dust can be seen. And from this cloud of dust individual spots start emerging in front of galloping riders, these are the poor foals that cannot yet run fast enough, and soon, when their strength is drained away, they remain behind the herd. They stop, with their nostrils flared by exhaustion and fear, frantically panting, and they are caught by a loop connected to a pole.” Let’s mention that many adult horses were shot down during that process…

It is curious that Grieger was successful beyond expectations, and because the original order was only for six foals, he drove two thousand kilometres on horseback (plus four days on a boat) to send a telegram to Hagenbeck with a question if he would be allowed to bring more horses to Europe. He was. In the end he set off for the return journey from Kobdo with 52 foals.

If the capture of Przewalski’s horses itself was apparently a horrifying spectacle, the transport of the foals was as just bad. Hagenbeck writes: “A large caravan that includes besides the captured animals their wet nurses (mares of domesticated horses – a note of M.B.) as well as animals transporting the travellers and their luggage, and thirty hired natives sets off for the long journey home. Heavily worried about the lives of the young animals Grieger slowly advances across mountains and valleys, in rain and sunshine, in heat and cold, to the nearest place connected to the world. In many mountains regions there is warmth of thirteen to twenty degrees during the day, while at night the temperature drops to the freezing point. For many of the young animals the hardships of the journey are too severe, they perished on the way despite all the care.”

Just the journey from Kobdo to Ob, from where it was possible to continue by boat, took according one of the later accounts fifty days. Pairs of foals were carried by camels. It is surprising that 28 alive foals of Przewalski’s horse arrived at Hamburg on October 27, 1901.

Two from these twenty-eight foals – a stallion later marked 11 M Biysk and mare 12 F Biysk – were purchased by Emperor William for the Agricultural Institute of Halle University. Two decades later the grandchildren of this couple of horses arrived at Prague: first the stallion Ali on October 17,1921, followed by the mare Minka, on January 21, 1923.

An aerial shot of Orkhon river in Mongolia

4) The Return of the Wild Horses – Heading East!

As soon as we arrived in Ulaanbaatar, the director of the Great Gobi B Protected Area, our long-time collaborator, Ganbaatar, gave me the best news I have heard since our transports of Przewalski’s horses started in 2012.

A third-generation foal has just been born in this reserve in western Mongolia! Shivers ran down my spine… In 2012, we transported four Przewalski’s mares from Prague to the Gobi by CASA military aircraft. One of them was Anežka. She had a daughter, Dodo, who gave birth to a filly, Sunder. Well, Sunder now has her own foal, Anežka’s great-grandson!

Naturally I was yearning to head west as soon as possible, to the Gobi B, but we’d flown to Mongolia to go in the opposite direction, to the easternmost part of the country. Why? When I was writing this column in Ulaanbaatar, there were exactly 938 Przewalski‘s horses in Mongolia (including the 100 foals born this year). They are found in Gobi B and Khomyn Tal in western Mongolia and in Khustain Nuruu in central Mongolia. This successful return of Przewalski‘s horses to Mongolia began in spring 1992, when two planes carrying “Przewalski‘s” from Europe landed in Ulaanbaatar shortly after each other – one with a shipment of horses for Gobi B and one for Khustain. However, there is a certain irony in the fact that much earlier serious consideration was given to returning the Przewalski‘s horses to eastern Mongolia. It never happened and only now is it being planned – by Prague Zoo in cooperation with many Czech and Mongolian organizations.

Just two days after our Ulaanbaatar meeting with Ganbaatar, we were criss-crossing the steppes of eastern Mongolia in off-road vehicles. We had returned to the Dornod area after more than two and a half years. This time, however, we were in far greater numbers. Not even COVID had stopped us working on our plan to return the Przewalski‘s horse to eastern Mongolia. Several Mongolian experts had gotten onboard – and now we finally had the opportunity to meet up and assess the pre-selected sites together.

Will there be suitable food for the horses? What about water sources? Where do the herders’ families live and where are their wintering grounds? What sort of profile does the terrain have and what are the winters like? What diseases might the Przewalski‘s be exposed to? Etc. etc. It wasn‘t always easy – for example, even the venerable professors were up to their thighs in mud to extricate a Toyota that had got stuck in the bog – but all in all, it was a great success. Next time, we will only take in two sites. One, with its scattered pine groves, is near the battlefields of the ‘opening battle of World War Two’ at Khalkhin Gol. The other, where bright yellow poppies were in full bloom at the time of our visit, is somewhat further southwest, near the Snake River.

There is still endless work ahead of us, but we believe that within a few years the Przewalski‘s horses will also return to eastern Mongolia. And I hope that one day I will see the foals of Anežka’s xth generation of descendants in the steppes there.