Run? Then run for a hospice and go there to see for yourself

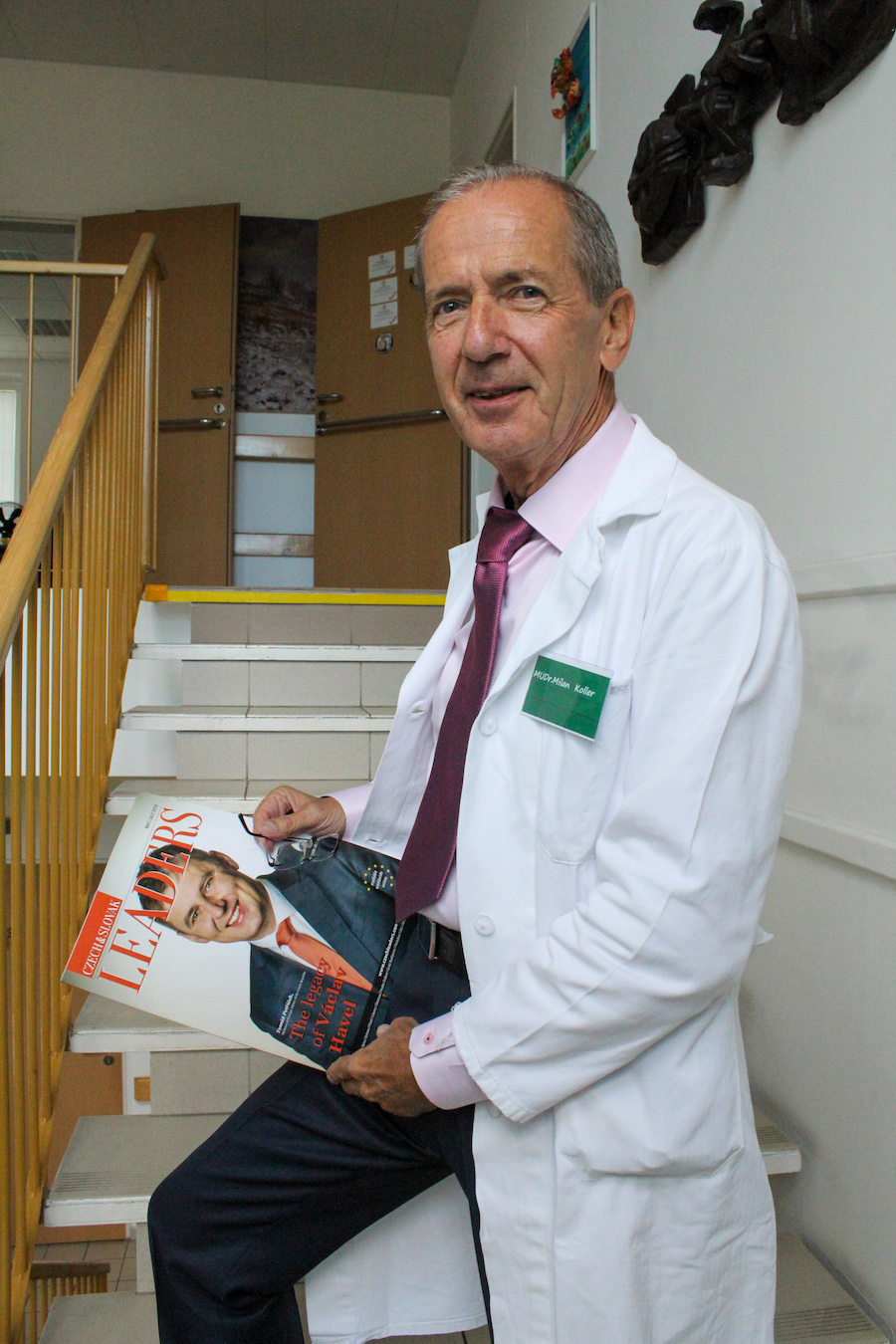

MUDr. Milan Koller

MUDr. Milan Koller is very much the Renaissance man from today’s perspective. At 65 years of age, he took partial retirement. Over the three years since, he has accomplished previously unfulfilled dreams. He has acquired a Group C, D and E driving licence (for large goods vehicles, buses and trailers). Through his friend, a transport company maintenance worker, he found out that the hospice in Most was looking for a doctor. He took the decision to offer his help to the hospice, and he now works there as chief physician. He has learnt to speak German fluently and is currently preparing for an advanced examination at C1 level. He has begun running marathons. And in order to give greater meaning to his hobby, he has set up the “Běhej pro hospic” (Run for Hospices) movement.

During his standard week, he manages to work in two gynaecology clinics, drive a bus for two city public transport lines, undertake medical services at the hospice in Most, and of course he also regularly runs and organises support for the hospice. His daily routine, character and mission is best portrayed in a short amusing video available on YouTube, entitled Běžím pro hospic (I run for the hospice).

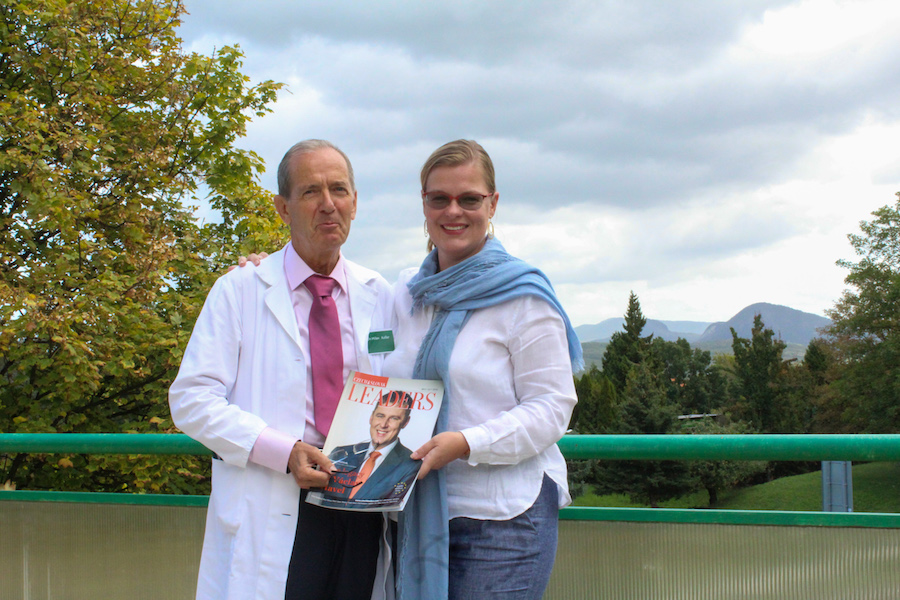

Despite his successes and ambitious plans, MUDr. Koller is unassuming and humble. He was surprised to be asked for an interview for Leaders magazine, and he doubted he was a sufficiently important figure. This was the first time I have experienced such a response in over two hundred interviews I have undertaken. I subsequently received a number of long, congenial and very open and personal e-mails, one in German. I received an invitation to visit the hospice for lunch. And so I set out with our photographer, Tereza … Have you ever been inside a hospice? I’d guess not. How do you picture it? A gloomy atmosphere, dark rooms and a depressing atmosphere of the presence of death?

The good doctor says that you have to experience a hospice. Few can talk about them. I will at least attempt to describe my own experience. Most’s hospice sits next to a beautiful park. The sun was shining and we had the opportunity to observe its smiling staff and the cheerful good doctor. Director Blanka Števicová is not just the director and manager of many years’ standing, but also a renowned cook. I will long remember her chilli con carne. As I will the fact that every year the hospice has to acquire 44% of its budget from grants, gifts and charity donations. It costs 16 million CZK a year to run the hospice. 44% of costs are covered by insurance and 12% is paid by the clients themselves, and so the Director has to take on another role as magician in order to procure the remaining 44%. Over my whole time there, I felt the special energy of this place, where time flows differently. I felt a slowing of time, and also a fundamental need to get to the heart of things in my interview, right down to the very core.

Doctor, let’s begin with a question which I’ve taken from the popular film, The Intern. The seventy-year old star, played by Robert de Niro, becomes an intern at a company full of people under thirty years old. The recruitment officer poses him the question: Where do you see yourself in ten years? Over the past three years, you have managed to retire, change your medical specialisation, run marathons and acquire a Group C, D and E driving licence. So where do you see yourself in ten years?

Long-term plans are for the young and middle-aged generations. I don’t ask myself that question. I think in terms of this year and next year. For me, retirement was a watershed. I thought long and hard about whether to focus on my hobbies and perfect them, or whether to take a more complex path in which I can do something of benefit.

Hold on, I don’t get that. You’ve been a doctor your whole life, an occupation that is one of the few professions which is not just a job, but rather a calling.

Exactly. Doctors can be doctors, and often cannot do anything else. I considered my new expanded driving tests as an opportunity to demonstrate that even doctors can do something else. Doctors often perceive themselves as a special category, even amongst themselves. When I got my Group C, D and E driving licence, i.e. for lorries, buses and trailers, I felt the need to succeed because I am a doctor. I was also worried about causing an accident and killing someone. I was worried that headlines in the tabloid media would be sure to include the fact that it was a 66-year-old doctor who had killed someone. I originally wanted to drive a lorry or trailer, but my desire for a part-time position prevented this. But this isn’t a problem for a city bus driver. When driving my bus I am fully focused yet relaxed at the same time. I perceive people and their worries, but also the beauty of the local landscape.

You are far from the usual negative stereotype of Czech pensioners, often described as passive, unwilling to learn, in poor health…

I don’t need to be a model. I can see that many factors influence one’s current state, such as one’s previous professional life, health and the many consequences of previous decisions. Many of my peers have problems, health-wise and money-wise, and that proverbial passivity is more a consequence than an underlying cause. I myself thus focus on making contact with people of the young and middle-aged generations.

You say you have to experience hospices. Why?

Today, hospices are highly taboo places. Long-term research suggests that 85% of respondents would like to die at home. 80%, however, will die in hospitals, nursing homes or in institutional care. The wish to die at home arises from a fear of dying alone in an anonymous environment without family and friends present. It should be acknowledged that this can occur in hospitals. Hospitals are not designed for dying in, but rather for treatment. The definition of a hospice means it has a different function. Citing from the website of our hospice in Most: “A hospice is a nursing-type healthcare facility that makes use of the findings of palliative medicine to the maximum extent. It is a system of services that promotes quality of life for the terminally ill. It practises a holistic approach to the ill, securing complete nursing, psychological, social and spiritual comfort. It offers a support system allowing one to live to the full to the very end.” It remains a paradox that were we to ask those respondents whether they want to die at home or in a hospice, the difference would be even greater; I’d estimate 90% of respondents would prefer to pass at home, and 10% in a hospice. Hospices still don’t have a good reputation.

We all want to die at home. Is that because we idealise death?

The option of dying at home would seem the best when so-called home hospice is available, in which doctors and carers are in close contact with the family and available when needed. On the other hand, this still involves reactive care, with changing shifts, and it isn’t always clear in advance how quickly deterioration can occur, and what burdens and complications care for the dying brings to those around them. I myself have witnessed acute requests for admission to hospice that we have unfortunately been unable to manage. Care for immobile patients is incredibly demanding, and it involves having to take care to ensure not just preventing bedsores, but also maintaining hygiene, correct medication and much more besides. Families can find this at the edge of, or even beyond their capabilities. You might be surprised that even palliative medicine has its own witticisms: “A doctor tells his dying patient: You’re not alone. And the dying patient responds: But I am.” And that’s true. We die alone. We should all acknowledge this truth. We are all afraid of facing death alone. But we will. I have seen myself that family members want to be with their loved one to the paradoxical end. They sit by the bed, but then they need to leave for a moment and that’s when their loved one passes. Don’t believe the films. Death isn’t the dying person uttering words of wisdom and then breathing their last breath. The process of dying takes a long time, and for the lay person it isn’t often easy to manage. On the basis of my own experience, I prefer the option of home hospice complemented by an acute bed in a normal hospice. You’ve had the opportunity to see our peaceful environment, and our terrace with a view for yourself, allowing not just close family members to be present, but also pets. Here, the doctor isn’t the most important element: the most important element is our carers. I myself experience great satisfaction when I do my rounds and I see that the patient at the very end of their life is still cared for, bathed, clothed and groomed: they are treated with dignity. It is often hard to recognise how close to death they are. This is all done very carefully without excess handling, which could worsen pain. Have you ever tried to bathe a 70-kilogram incapacitated person in an ordinary bath in an ordinary apartment? And then there’s enjoying the fresh air: many lifts still don’t take wheelchairs.

Is an older doctor a benefit for patients?

I sense that we feel closer to each other. Also the risk of burnout is much lower for me than it is for my younger colleagues. When I look back at my life, I feel that I’ve done what I wanted to do. I haven’t got any ambitions. Years ago, I got into yoga, which gave me the opportunity to experience the state of here and now, while also giving me the option of making a choice – good or bad. I have also opened up space for chance, which I consider to be the most wonderful thing in life.

Chance really does play a large part in your life. One chance in the form of your friendship with a maintenance worker led you to the hospice. Another chance in the form of a delayed salary payment led you to seek another way to fund the hospice.

The director came and explained to me that she first had to send out regular salaries to employees who existentially depend on it. I’m lucky in receiving four salaries and one pension. The next month saw me filled in on the details of funding and the sum of seven million crowns a year, which has to be liter- ally begged for each year. I could have made the decision to work for free, but I didn’t think that was a systematic solution. While training for the marathon, I came up with the idea of helping in a different way. Most training runs for the marathon are slow and boring. Over 18 weeks, you might run, for example, 10 km/hour a few times a week. Training for a marathon is necessarily boring, having to give your legs the right amount of training. I got an idea of how to elevate my running; how not to burn out as a runner. I achieved my personal record when I ran the marathon in 3 hours 46 minutes, and the half-marathon in 1 hour 45 minutes. I’m in the top tier in my age category. Any further improvement would require further strenuous effort. I didn’t want to improve my running, but rather give more meaning to my running.

And so your Run for Hospices activities began, which are today focused not just on supporting the hospice in Most, but also on supporting hospices throughout the Czech Republic.

And we return to our discussion on the fact that hospices have to be experienced. I endeavour to make contact with runners, who are separated by some distance from hospices. They are young, successful, well-off people with the best equipment, who share their experiences of foreign holidays before the start. So I thought I would set them the challenge of running for hospices. We give running greater meaning. If anyone happens to run slowly, they’ll still have a good feeling of contributing to a worthy cause. I came up with the idea that I would give 1 CZK to the hospice for every person I outrun. So I can be much more successful than the scoreboard might imply. I like Gandhi’s quote: Be the change you wish to see in the world. Last year, I ran the half-marathon three times and the marathon once. I calculated that I outran about 14 500 runners, so I gave a sponsorship gift for this sum to the hospice in Most. This year, I’m endeavouring to invite dozens of people to do something similar, to expand awareness of all the 14 hospices operating in the Czech Republic. I’m endeavouring to simplify the entire system. If people register for a halfmarathon or marathon, they can donate the same sum as the starting fee to a selected hospice directly. I’m also calling on them to hand over the sum in person, so that they can experience the hospice. You can’t form a relationship to a hospice merely by sending them money. That is only formed when you visit it. I cordially invite everyone to run to their nearest hospice while training. A lack of time is just an excuse. Running for a hospice gives your run greater meaning. It is entirely up to you when you join us…

By Linda Štucbartová