“Personal account OF THE PANDEMIC”

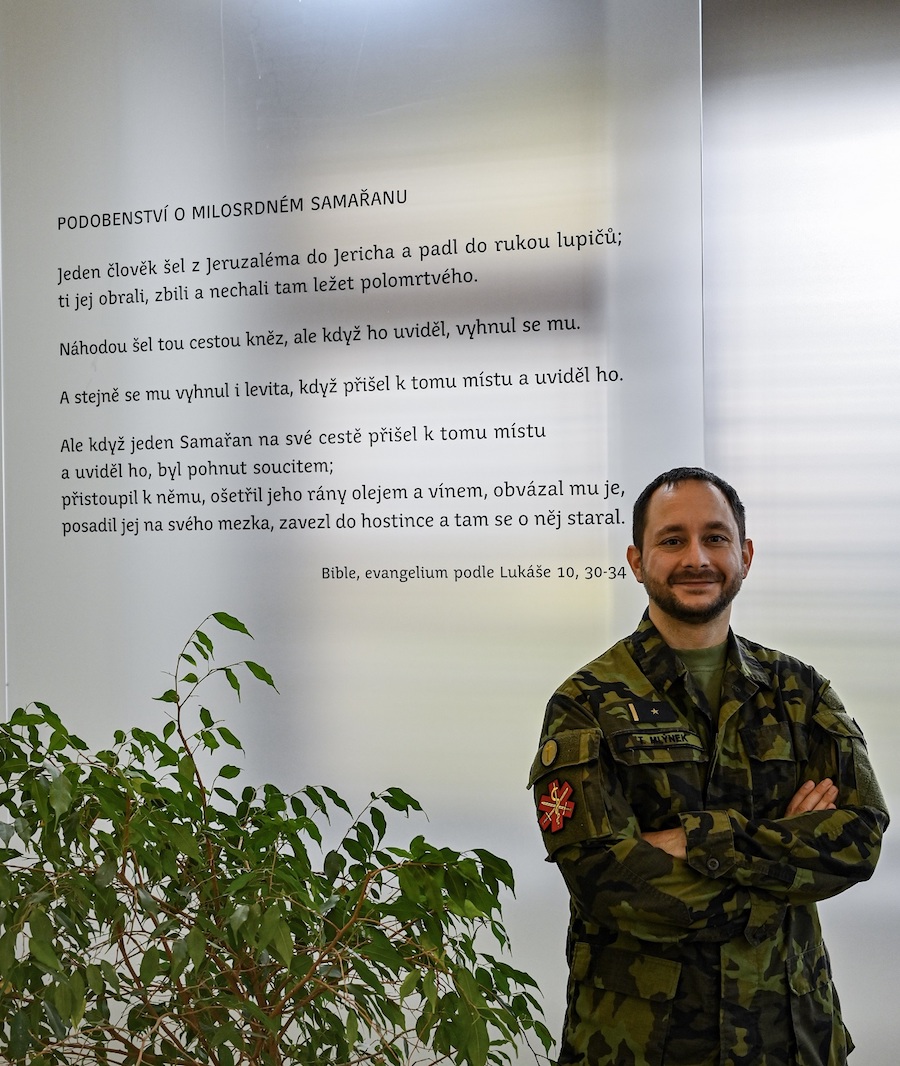

Chaplin Major Tomáš Mlýnek, Photo: KCVV Praha

The interview with Chaplain Major Tomáš Mlýnek will be my innermost contribution for a long time. It took place based on the experience of my husband, who met the chaplain after waking from an induced coma as a result of a severe case of Covid-19. Meeting the chaplain affected my husband very deeply, and helped him deal with the experience.

At the end of January, my husband’s mother died. Not of Covid, but definitely belonging among the statistics caused by Covid. The long separation from her immediate family, and the postponement of regular checkups connected with adjustments of medication, resulted in her weak heart simply being unable to cope with a relatively banal infection. Like many others, we didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to her in the hospital. And the red (!) handwritten inscription “Anti-epidemic system level 5, only 15 people permitted!“ in the ceremonial hall only expresses how much we’ve surrendered the basic values associated with humanity.

Three weeks later, my husband and I fell ill with Covid-19. After a week of being sick at home, we both got a complication in the form of pneumonia. My husband was hospitalised, and after two days spent in bed on oxygen, he was put in an induced coma with lung ventilation. He spent 10 days in this state. These days were among the most difficult of my life. How much strength the faith and prayers of those around me gave me is probably incommunicable.

Mjr. Tomáš Mlýnek, LTh, MA, has been a Roman Catholic Church clergyman since 2005. In 2009, he completed his postgraduate licentiate studies with a focus on bioethics and alternative medicine, and he also devotes himself to the issue of psychology and psychotherapy. He worked in several parishes in Moravia, in the territory of the Krnov deanship. Since 2012 he’s been Chaplain of the Army of the Czech Republic, and since October 2020 he’s worked as a military chaplain in the Central Military Hospital in Střešovice. Chaplain Mlýnek has experience from working in two foreign missions in Afghanistan. In his spare time, he has taken part in the ADRA humanitarian mission in Kenya three times.

The chaplain responded to the request for an interview literally immediately. And at the same time, he thanked me for the opportunity to be at my husband’s bedside. Before we started with the first question, the chaplain thanked me for the chance to talk about his work. You’ll notice that, in the interview, he talked about others more often than about himself.

Note: the article was written with my husband’s permission. I dedicate it to him, and all the paramedics and medical staff who saved his life.

Mr. Chaplain, before we get to you and your work, let’s talk about solidarity with paramedics and medical staff. As an expression of gratitude, I organised a cake baking event for medical staff at Rotary Club Prague International. Other people have resumed organising collections for healthcare workers. How are medical professionals doing?

At the start of the pandemic, there was huge solidarity and people felt the need to show their sense of togetherness with healthcare workers. I understand that a year has passed, and people are tired. There is also less money. But unfortunately the solidarity has also vanished. People forgot that healthcare workers have literally been in a large-scale engagement for a year now, and there are several times as many patients as last spring. I’m not talking about finances. I’m talking about letters, pictures from children and the proverbial baking. Medics really appreciate any expression of solidarity for their commitment and perseverance, and it helps them cope with this difficult period.

Are we at war with Covid? Soldiers who worked in foreign missions and are now helping out in hospitals said that deployment in hospitals is much more demanding than deployment in military operations.

Military deployment is different. It has a time limit. You set off on a mission, and you know you’ll return home in six months. Because we don’t have a prognosis for the end of the pandemic, the feeling of the end is much more distant. I don’t want to talk about war, because they say that war has no winners. There are always only the defeated, due to the losses connected with the conflict. I want to believe that we’ll come out of the pandemic winners. I believe that we’ll learn. Everyone experienced some restrictions, pain and limits during the pandemic. That’s why I’d rather refer to it as a battle. And there’s another difference here. In a war, people can close ranks against the enemy. I feel that because of the division of society, including various political and professional views, we’re not united. We’ve lost the ability to pull on one rope, which was so visible at the beginning of the pandemic. To not look for side alleys, and simply abide by the rules. To hang in there. Humans have the ability to adapt, but that goes hand-in-hand with a decrease in attention and vigilance. We get used to things, and stop perceiving danger. It is this attitude that poses the greatest threat.

How has the nature of your work changed during the pandemic?

I’m often asked this question. The amount of work has increased. People’s health is much more at risk. In additional to normal care for patients, whether inpatient or outpatient, we provide the same amount of care for hospital staff. Not only are healthcare workers affected by problems arising from long-term pressure and exhaustion, they also face problems at home. Their own children are studying online, their partners have often lost their jobs, and they’re afraid for their loved ones. The level of pressure healthcare workers are exposed to is enormous. There is of course also a difference in the amount of regulations that must be followed, and the use of protective equipment.

The level of pressure has surely affected you too. Patients cannot see their relatives, and visits are significantly restricted – permitted only for patients in the terminal stage of illness. Together with the staff, you form their only connection with the world.

Yes, that’s true. Family members also make use of this, when they call us and ask about the patient’s condition. We’re not authorised to disclose a diagnosis. But we pass on greetings. We communicate how people are feeling. I had a case of a man hospitalised in the Covid department, who was unable to make a phone call. I helped him talk to his wife. Every call can be encouraging for the patient. You’re going there not with the intention of examining the person, but of asking them how they are. A huge misunderstanding of the essence of a chaplain’s work can be summarised in a sentence which I often hear: “I’m not dying, so I don’t need a priest.“ In a hospital, we’re all trying to help the patient recover and return home. All care is therefore aimed at encouraging and activating the patient. For years and years we’ve been trying to change the impression that the clergy is associated only with the ritual of the last anointing, or the end of man.

We probably have an idea of what a chaplain’s work looks like. How would you briefly explain its essence?

The essence of a chaplain’s work is about the establishment of work with values and the meaning of life. It’s not missionary work, connected with spreading the faith. I am, I should be, an expert in spirituality.

When presenting our work to new doctors and healthcare workers, I work with Maslow’s pyramid of values. For many years, Maslow claimed that the last stage is self-realisation. Before the end of his life, he added one more level to the pyramid, which he called self-transcendence; figuratively, the search for the meaning of life, or spirituality. He therefore pointed out that this is the culmination of human existence, which affects all other areas. What is the meaning of my life? What direction do I want it to take? How do I perceive values that are universal for every human being, such as friendship, forgiveness, life and death? The essence of a chaplain’s expertise is to open these values, and work with them so that the person in question addresses them. Initially, we don’t talk about faith at all. We come to it gradually. We don’t talk about religion. We talk about what the person is experiencing here and now. Literally, in the sense of what could help the person in question; what they breathe here, and what they’ll be breathing at home.

The word “chaplain“ used to refer to those starting out in the clergy. Today, it’s used in the sense of a person who is designated for a given category of people. So we have military, hospital and prison chaplains, chaplains for youth and seniors, and chaplains for people at the margins of society.

I myself am used to being addressed as chaplain. In the army, the address Padre is used, as in the MASH series. We also have a female military chaplain, who they call Madre.

Let’s now move on to my husband’s experience. He was very grateful for your bedside visit after he woke up from the induced coma. In the conversation with him, you mentioned that patients who lose their breath also lose their spirituality.

The Covid disease seems very symbolic to me in that it attacks the human respiratory system. If we consider spirituality in the sense of the word spiro, or breathing, then the virus attacks that which our interior breathes through. As soon as you’re connected to a ventilator, you give up your life, because the device breathes for you, so you actually lose control of your existence. The one thing we desire is to have our life in our own hands. And suddenly the person is very defenceless, helpless and vulnerable. And that’s what creates space for us. We visit departments where people are in an induced coma, and we pray for them. So that they can continue breathing. So that they can take control of their lives. So that the virus doesn’t win, so that their spirituality returns.

What’s happening is very figurative. When I look at our society, I feel that it has forgotten to live its own inner life. We’ve forgotten to live in the present. We’re forgotten our inner values, we’ve forgotten to breathe. What we can gain from this battle is a return to those values. And the greatest value is what we all have. It’s our lifetimes, which we pay for everything with. I ask recovering patients: what will be your next step? What are you leaving the hospital with? I try to encourage them to pay attention to what it is in their lives that they pay for with the one thing at their disposal. Their lifetimes.

I can confirm that. After the conversation with you, my husband called not only me but also the children. He told us all that he loves us, and wants to spend more time with us.

I’m glad to hear that. This reassessment of values often occurs after such an extreme experience. The patient realises that value isn’t based on what I do, how well I do it or how many titles I have… the only value is in that I AM. I’m a human being. If I manage to awaken this value in someone, and they go home with this mindset and pass it on to their loved ones, then I considered my work meaningful and justified. And I’m grateful for it. You can see for yourself that this work has nothing to do with any religion or faith, yet it involves values that are common to us all. We come to faith gradually. I wait for the person in question to ask me about my faith.

I mentioned that many people prayed for my husband. You did too, and thank you very much for that. I also came across the opinion that some would like to pray, but they don’t know how… I think that everyone is able to pray sincerely. Or not?

Religion, faith, churches and spirituality are surrounded by much false ballast. Prayer is an essential element of the relationship between God and man. Everything that’s an expression of the relationship between Him and me becomes a prayer. The way you love your husband, the way you’re close to him and say something nice to him, is itself a form of prayer. Whenever I think of another person positively, whenever I relate to some entity, whenever I perceive the need to express goodness, I’m praying. Anything that’s carried by love is a prayer. It’s a natural heart-to-heart dialogue. And we’re all capable of this foundation. Prayers in the form of texts are defined by ritual, for example to make easier a collective prayer, or moments when we’re lost for words… but words don’t matter. It depends on what’s in the heart,and the goal itself. If the goal is good, then it’s a prayer. That’s why I offer a blessing. In Latin, a blessing is called benedictio, or to speak well. If I wish you well, then I’m blessing you. I’m praying. So truly anyone can pray, it’s just sometimes they don’t know what to imagine behind it. I tell people that if you work honestly, for the greater good, then you also pray through work. And it doesn’t matter whether you’re cleaning the floor, standing behind a desk or injecting people. You can live a spirituality that’s reflected in what you do when you put your heart into it.

Mother Theresa herself said: “It’s not what you do, but how much love you put into it“. Love then prevents us from falling into an extreme where work becomes our idol. There’s love for others, and self-love. And self-love should prevent us from harming ourselves. People who are fixated on performance fall into a trap, because they lose out on relationships and the experience of beautiful things. That’s no longer prayer. In that case, somewhere inside us we’re missing the mindset that a human being’s highest value is that they ARE. Without them having to do anything.

I think that the afore-mentioned words could serve as final ones. But I feel you still have something to say.

It doesn’t matter what a person is doing or where they are. It’s enough to develop the basic vocation they have. Being human. I’ll never be a completely good husband, father, lawyer or president, or a good wife or mother, if I’m not fundamentally human. Becoming human is a lifelong process. The fact that I’m born a human doesn’t mean I’m human. I spend my whole life learning to be human. Let’s not give up this learning. Let’s try to be more of who we are. In Christian anthropology, we were created in God’s image. As people. That’s the basic human vocation, and the basic dimension of spirituality. Everything else is an extension. When the image of humanity in us is damaged, it will be reflected in everything we do, and that would be a great pity.

Linda Štucbartová