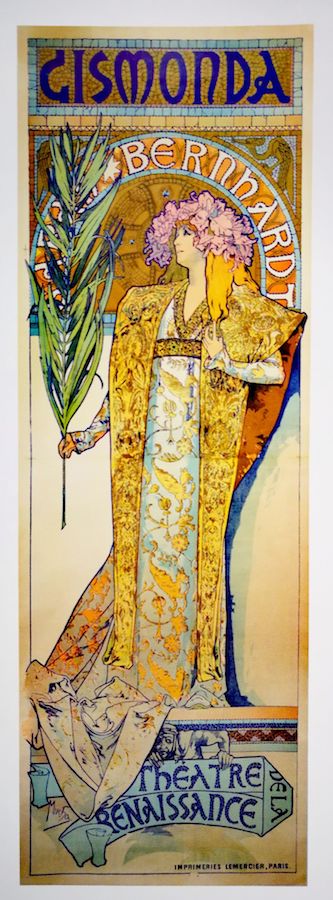

Gismonda poster, 1894, starting point of Mucha ́s career in Paris

“The purpose of my work was never to destroy but always to create, to construct bridges, because we must live in the hope that humankind will draw together and that the better we understand each other the easier this will become. I will be happy if I have contributed in my own modest way to this understanding, at least within our Slav family.”

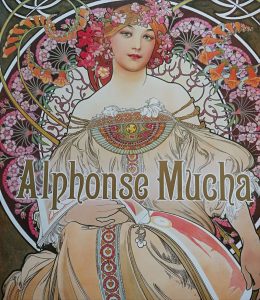

Virtual illustrator and monumental painter, renowned Parisian artist and convinced Czech patriot, Alphonse Mucha, it would seem, lived a hundred lives, and he did so particularly intensively during the Art Nouveau period.

All it took was just one poster to make him the most fashionable Parisian artist at the end of the nineteenth century. But what a poster! Portraying the “divine Sarah Bernhardt” as Gismonda, the role she was playing in Victorien Sardou’s play, Alphonse Mucha could not have remotely imagined it would launch a style which would bear his name. It sounds like a fairytale. Mucha, who had left his native country at the age of 17 to slowly build up somewhat of a reputation as an illustrator, on Christmas Eve 1894 while working at a publishing house discovered that the actress required a new poster for Gismonda which had to be ready before the New Year. Mucha, 34 years old, did not hesitate, created his poster and immediately sent it to the artist at the Théâtre de la Renaissance. The famous actress was thrilled by the result, wanting to meet Mucha immediately, and shortly thereafter signing an exclusive six-year contract with him giving him ten times the earnings he had made at the Lemercier publishing house. The artist ordered posters, theatre decorations, costume designs and a number of pieces of theatrical jewellery.

Overnight, the whole of Paris was enthused by the new artist, and people even cut off the corners of his street posters as keepsakes. What was it about Mucha that captivated people so much that he deposed leading artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules Chéret, previously undisputed masters of poster artistry?

Mucha’s new format was an innovation; an almost life-size poster, and so especially was his portrayal of a woman with an ethereal silhouette, with lilies in her hair and a gold hair-band, the figure of a woman from the Byzantine world and also a flower-adorned muse. In particular it was his new palette of colours, far removed from the usual rich bright tones. His posters stood out with their new palette of pastel colours and incredibly fine nuances of blues, greens and pinks, etc…

Mucha and his family, wife Maruška Chytilová and children Jaroslava and Jiří in Zbiroh, 1917

This poster was followed by 9 further posters: La Dame aux Camelias, Lorenzaccio, Hamlet, Medea, La Tosca, Orlík, and others. Mucha’s career was launched. He became famous because he was different. His thick haired Slavic girls enchanted with the freshness and joy of beautiful youthful women, Slavic princesses embodying the feminine ideals of the Art Nouveau period.

Even before Bernhard, however, the young Mucha had already experienced life as an artist. He had been employed at the age of 19 in Vienna as an apprentice scenery painter in a company which made theatre sets. He had also worked for Count Khuen-Belasi for three years decorating Emmahof Castle and the Count’s brother’s residence in Bolzano. Khuen-Belasi funded his studies in Munich (1887) and later the Academie Julien in Paris, where he met Bonnard and Sérusier. He found life in Paris inspiring in many ways. He admired Japanese art and esotericism. In 1898 he was admitted to the Freemasons. He was interested in photography, modernism, and met the Lumière brothers. He was keen on Rodin, and Paul Gauguin became a close friend.

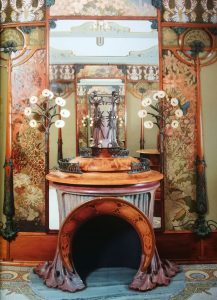

Goldsmith George Fouquet ́s boutique interior, 1900

He was a versatile artist, with his art in high demand. He worked with leading goldsmiths, and his drawings adorned Job cigarette packets, Lefevre-Utile wafers, Ruinart champagne and Meuse beer. His work was to found on calendars, restaurant menus and ordinary posters decorating the home. He made a lot of money for those who used his work to advertise anything at all they were selling.

At the turn of the century, he received a commission from the Austrian government to decorate the Bosnia and Herzegovina pavilion at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris. This job led him to consider dedicating his artistry and talent to his homeland. A few years later he realised his dream and the famous Slav Epic was produced, a series of twenty monumental paintings. In the end, he found a backer for the work in the USA, where he regularly travelled and taught between 1904 and 1910. Although Mucha was a cosmopolitan artist and polyglot, he remained a committed patriot his whole life. One should bear in mind that the political context of 1890 meant that Mucha was officially a citizen and artist of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and his homeland of Moravia was not recognised as an independent state at that time. The Czechs had lost their autonomy in the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, with the Czechs living under Habsburg rule until the end of the First World War in 1918 when the Czechoslovak state was formed with Tomáš Masaryk as its first President, someone who was also close friends with Richard Crane, a millionaire, admirer of the Slav culture and an influential American politician. It was Crane who provided the financial support which enabled Mucha to produce the Slav Epic.

Dream, color lithograph, 1897

Mucha finally returned to Prague in 1910. In 1918 he designed the first bank notes and postage stamps for the new independent Czechoslovak state. A major job he undertook was the decoration, furnishings and interiors of the Municipal House in Prague, completed in 1926. In 1931 he designed two famous stained-glass windows for St Vitus Cathedral in Prague Castle, showing the sages Saints Cyril and Methodius.

Shortly after the Czech Republic’s occupation by Germany in 1939, he was imprisoned by the Gestapo for his covert nationalism. As a result of his imprisonment and suffering, he died in Prague a few months after his release.

Author: Ing. Arch. Iva Drebitko; Photos: author’s archives

Note: the Alphonse Mucha Exhibition can be viewed in the Musée du Luxembourg, 19, rue de Vaugirard, 75006, from 12 September 2018 to 27 January 2019

Sources: Press release on the opening of the Alphonse Mucha exhibition in Paris, 11 September 2018. Interview with John Mucha, Alphonse Mucha’s grandson.

Photos: Press release on the Alphonse Mucha Exhibition in Paris, September 2018.