Soon it will have been two years. Each day then I snorkelled in the Red Sea trying to see (and possibly also take a photo of) as many animals as possible. Every evening I wrote a note about what interested me the most. Hawksbill sea turtle, a huge school of mackerel, dugong… Only one day – 18 October 2021 – I had not written anything. But now I was unexpectedly reminded of this very day through the iNaturalist network.

That day I was already returning to the shore when I saw a strange object just below the surface of the water. First, I thought that it was a piece of plastic, but immediately I realized that it could be some kind of organism. So, I took one photo and in the evening I uploaded it to iNaturalist. Unfortunately, its artificial intelligence extraordinarily had not offered me any hint at all, so my photo remained without any identification.

This has finally changed now. The marine biologist, Alejandro Escánez, from the University of Vigo in Spain, identified it as the eggs of diamond squid.

Once more: S-q-u-i-d!

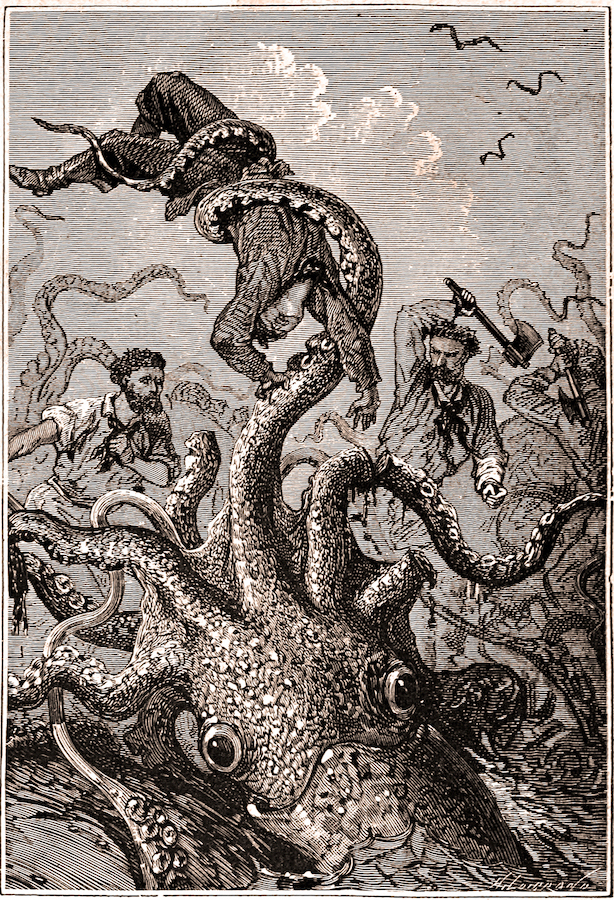

Of course, my schoolboy years immediately jumped in my head, when I devoured Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea:

“But hardly were the screws loosed, when the panel rosed with great violence, evidently drawn by the suckers of a poulp’s arm. Immediately one of the arms slid like a serpent down the opening, and twenty others were above. With one blow of the axe Captain Nemo cut this formidable tentacle, that slid wriggling down the ladder.”

Although Jules Verne writes about a poulp, the memorable engravings by Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou depict a squid; not to mention the fact that Verne himself referred to a story of the corvette Alecton, which tried to hunt down a two-ton giant squid in November 1861 (this was probably a huge overstatement, however, the truth is that this mysterious squid can reach truly fascinating proportions).

In the case of my observation, it was not the eggs of the giant squid, but the significantly smaller diamond squid; however: How often do you come across a clutch of such a strange, downright iconic creature?

“My” diamond squid can measure over one meter without the tentacles, so it is no little thing either. Moreover, it is remarkable in other ways, such as by its clutch. The female lays it by paired oviducts and at the same time she excretes a secretion, which connects them in a helix into phosphorescent tube with a diameter of ten to twenty centimetres and length of up to two metres. This twisted cylinder can contain tens of thousands of eggs – and when a diver very rarely comes across it, immediately wild speculations arise about what it could have been. At the same time, however, the record of each such a clutch is a valuable proof of the presence and reproduction activity of diamond squid in the area.

So in summary: The identification of the object on my almost two-year-old photo, confirmed also by a specialist in cephalopods, really pleased me and improved not only one, but several of my days.

Miroslav Bobek